Don't just do something, stand there! Analyzing timeout strategy in college volleyball

A deep dive into the impact of coaching timeouts in NCAA women's volleyball

Volleyball and basketball are two sports where you will often see one team go on an extended scoring run. And as those scoring runs persist, you can almost feel the pressure on the opposing team’s head coach to do something. And so eventually, inevitably, the coach will take a timeout to stop the bleeding, break the spell, cool off the hot hand, etc.

But does calling a timeout actually do anything? Does it help? In the NBA, Kevin Dewandeler took a systematic look at this recently and found little evidence that timeouts were effective in halting the momentum of an opposing team’s scoring run.

In volleyball, analyst Joe Trinsey looked at timeout data for Pac-12 games and FIVB games to see if there was any discernible benefit to calling a timeout to halt an opponent scoring run.

This post will cover similar ground (and come to similar conclusions), but relies on a far more robust dataset of all Division 1 NCAA Women’s volleyball games from 2022 to 2025. That’s 19,000+ matches and over 169,000 timeouts1. We’ll start with a look at when coaches call timeouts in volleyball, and then move on to their impact.

When do teams call timeouts?

Because there is no clock to stop, nor ball to advance to mid-court (as in the NBA), the most common use of timeouts in volleyball is to put the brakes on an opponent run. In volleyball, the team that serves is the one that won the previous point. So, a scoring run is in effect just a string of service points.

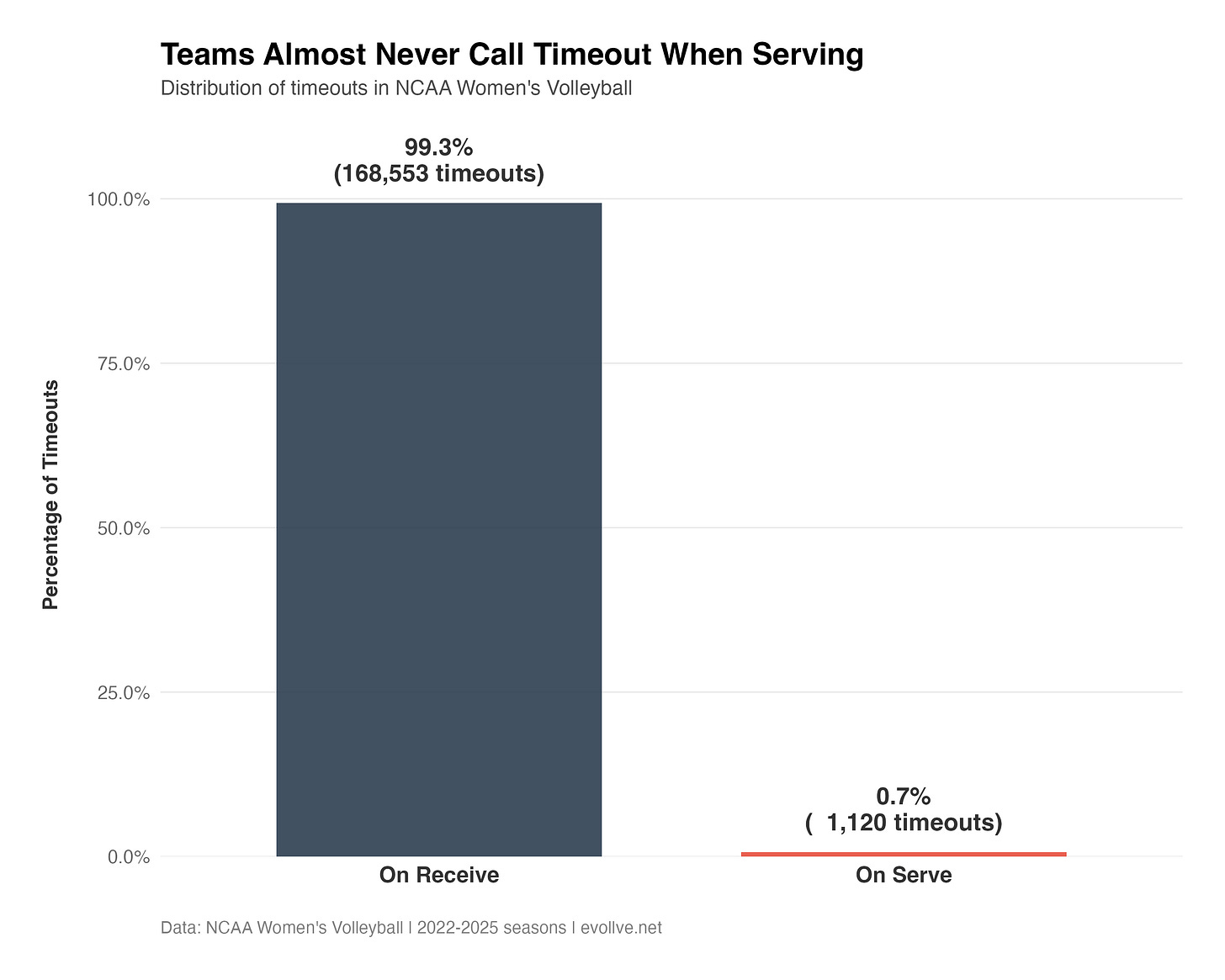

As a result, the vast majority of timeouts (>99%) in NCAA volleyball are called by the receiving team:

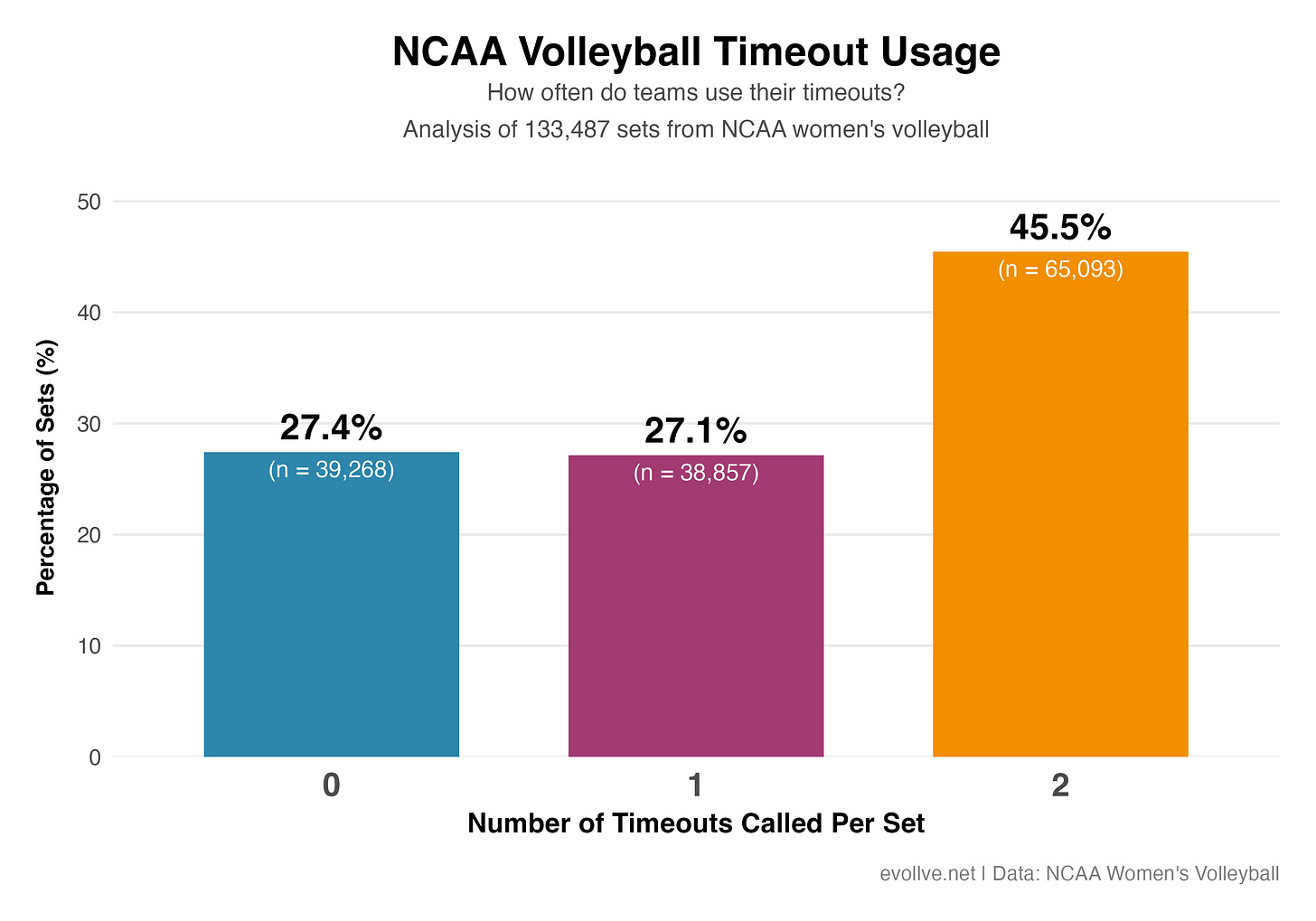

There doesn’t appear to be much “use it or lose it” pressure for timeouts, as more than half the time, coaches leave at least one timeout in their pocket:

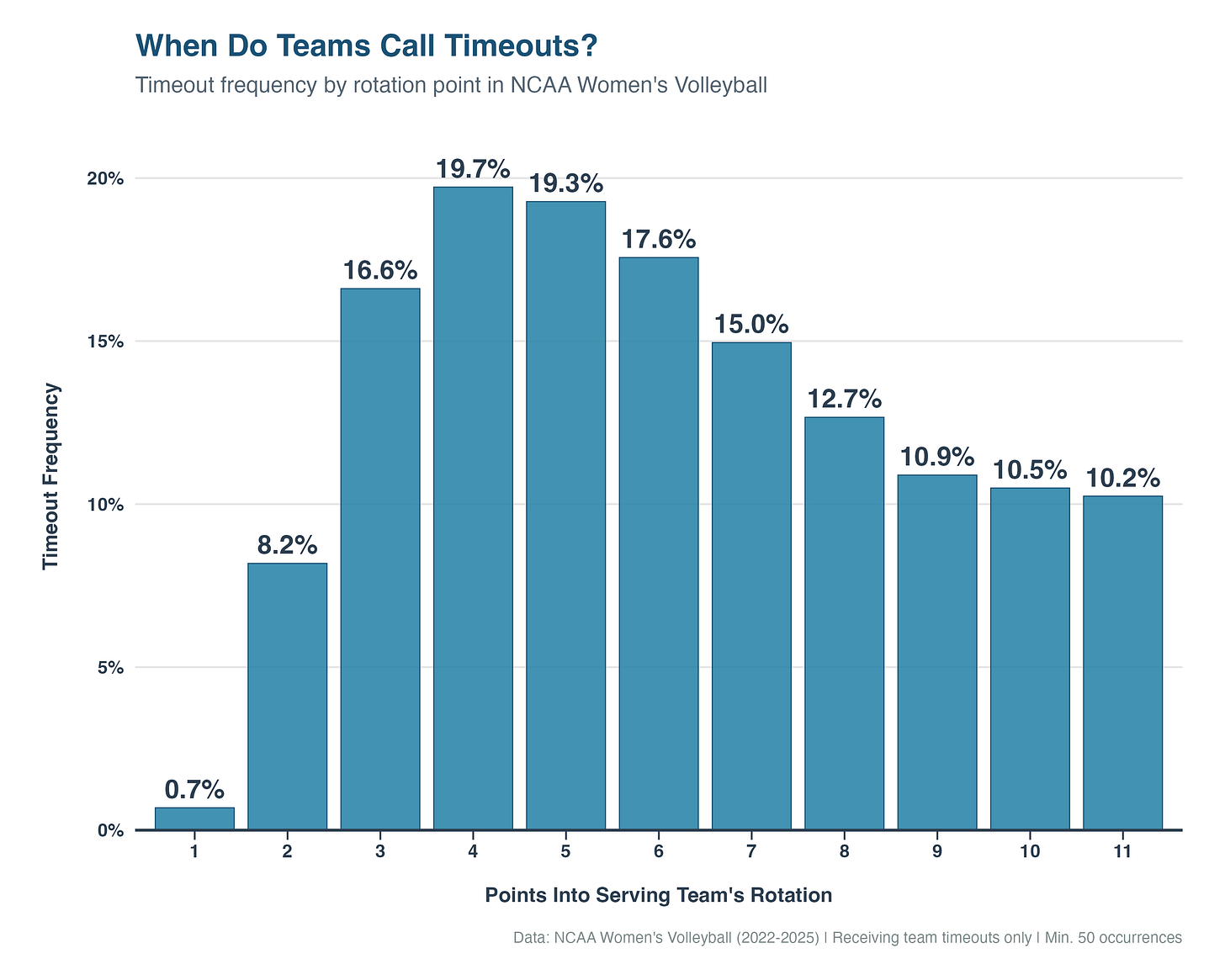

The longer a scoring run persists, the greater the pressure to call a timeout. Here is the likelihood that a timeout is called, based on how many points a team is into their serving rotation.

We see the likelihood peak at a scoring run of 4, and then start to decline. That doesn’t mean that the pressure to call a timeout starts decreasing, but rather it is likely that a team has already burned a timeout by that point in the rotation, and is not looking to burn another.

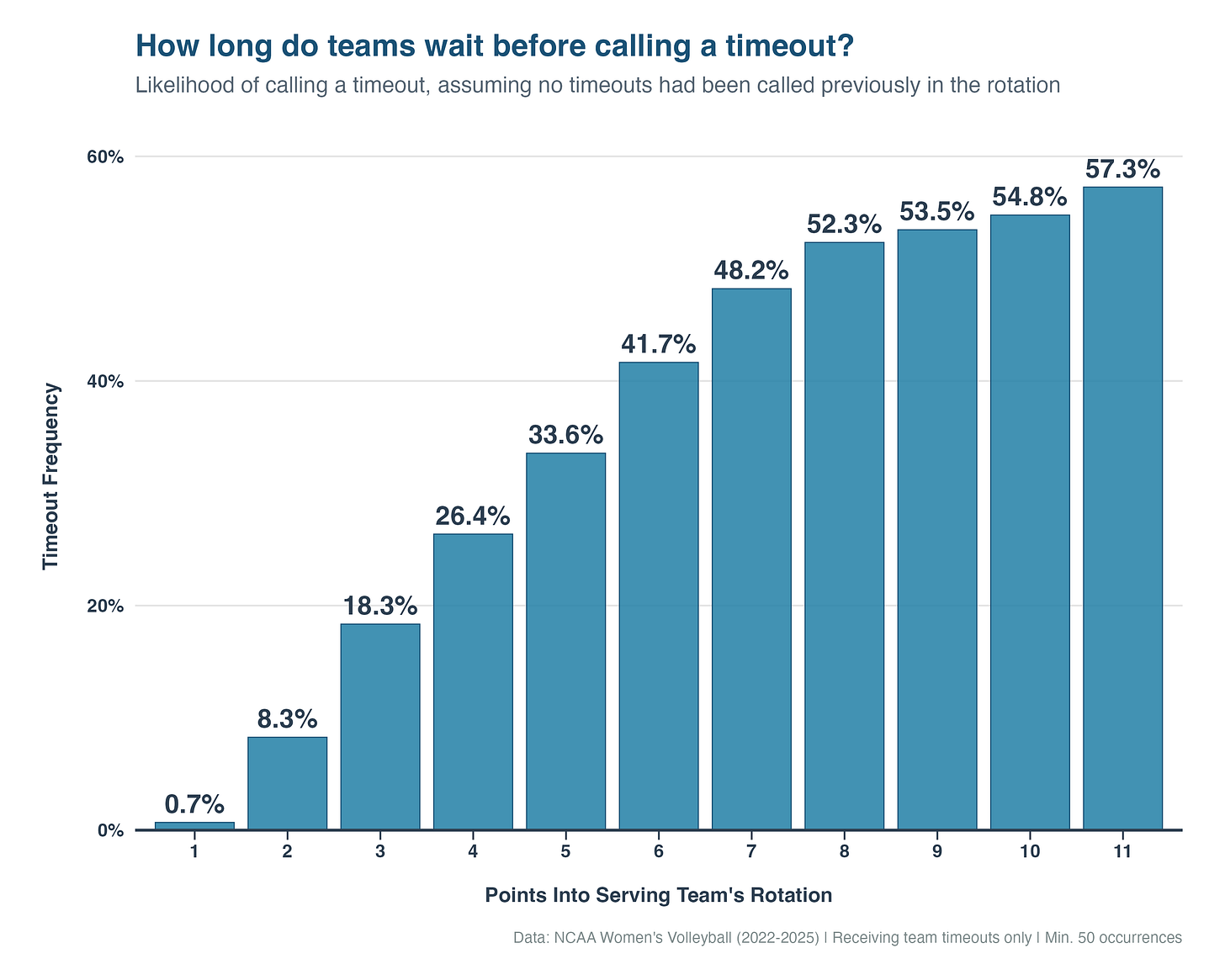

So, we can also look at timeout frequency just for situations in which a timeout had not been called previously in a rotation. Cut this way, we see steadily increasing likelihood of calling a timeout the longer a scoring run persists

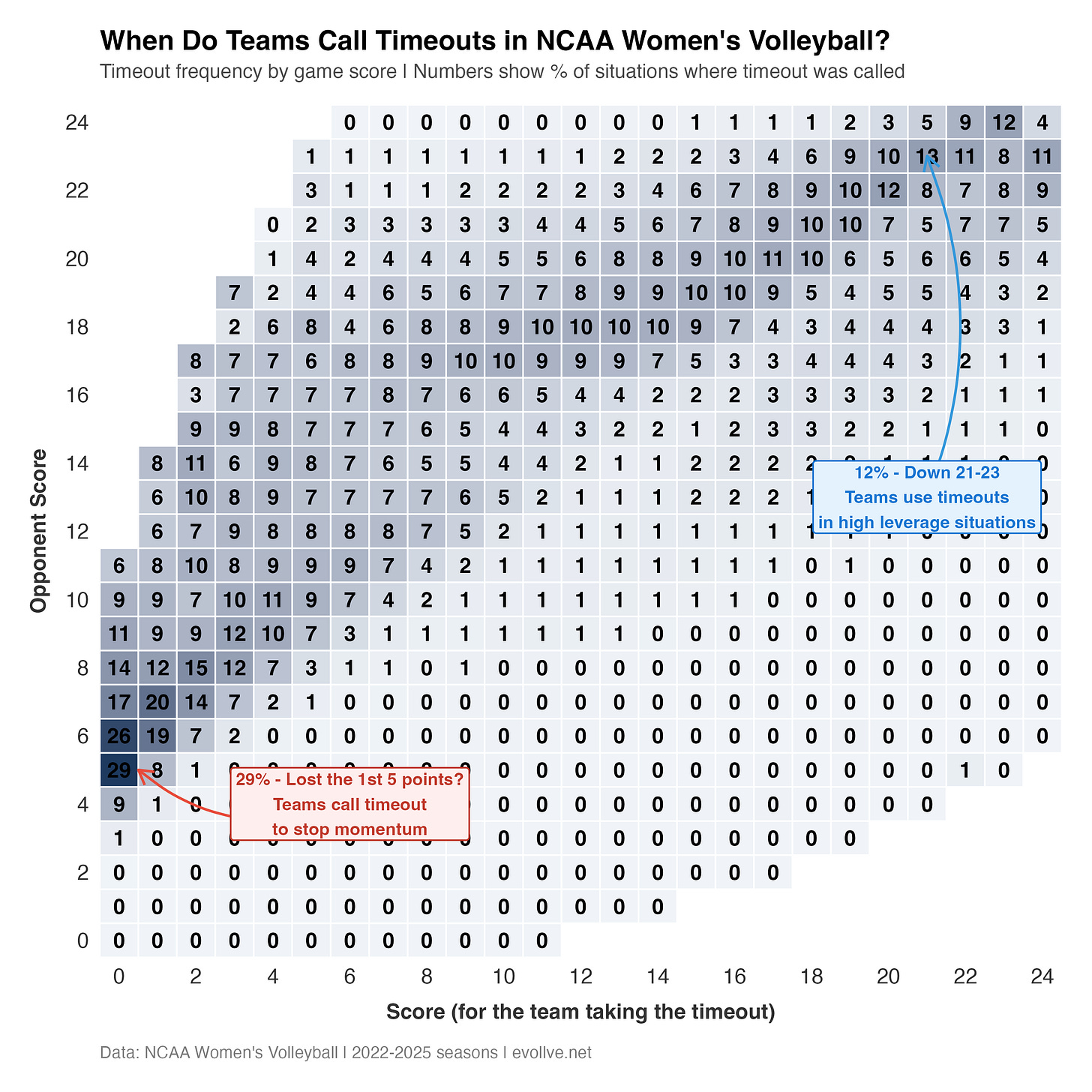

.Timeouts can also be game score dependent. Here is timeout frequency based on the actual score of the game (sets 1-4 only since set 5 is just played to 15 points).

A few patterns emerge here:

The most likely time to call a timeout is if your opponent opens the set on a 5-0 run (coaches call a timeout 29% of the time in that situation)

As one would expect, timeout frequency increases near the end of the set and in high leverage situations

Timeouts are significantly more likely to be called by the trailing team, while teams with a comfortable lead are in “if it ain’t broke” mode

Do timeouts help a team break an opponent serving run?

So, we have a good idea of when teams call their timeouts. But does it actually do anything?

The structured nature of volleyball scoring, and the vast amounts of data available for NCAA Division 1 women’s volleyball, make this a very straightforward problem to analyze. For each point in a service run, we can split outcomes by whether a team called a timeout or not, and then measure resulting success for the “took a timeout” situations versus the “no timeout” situations.

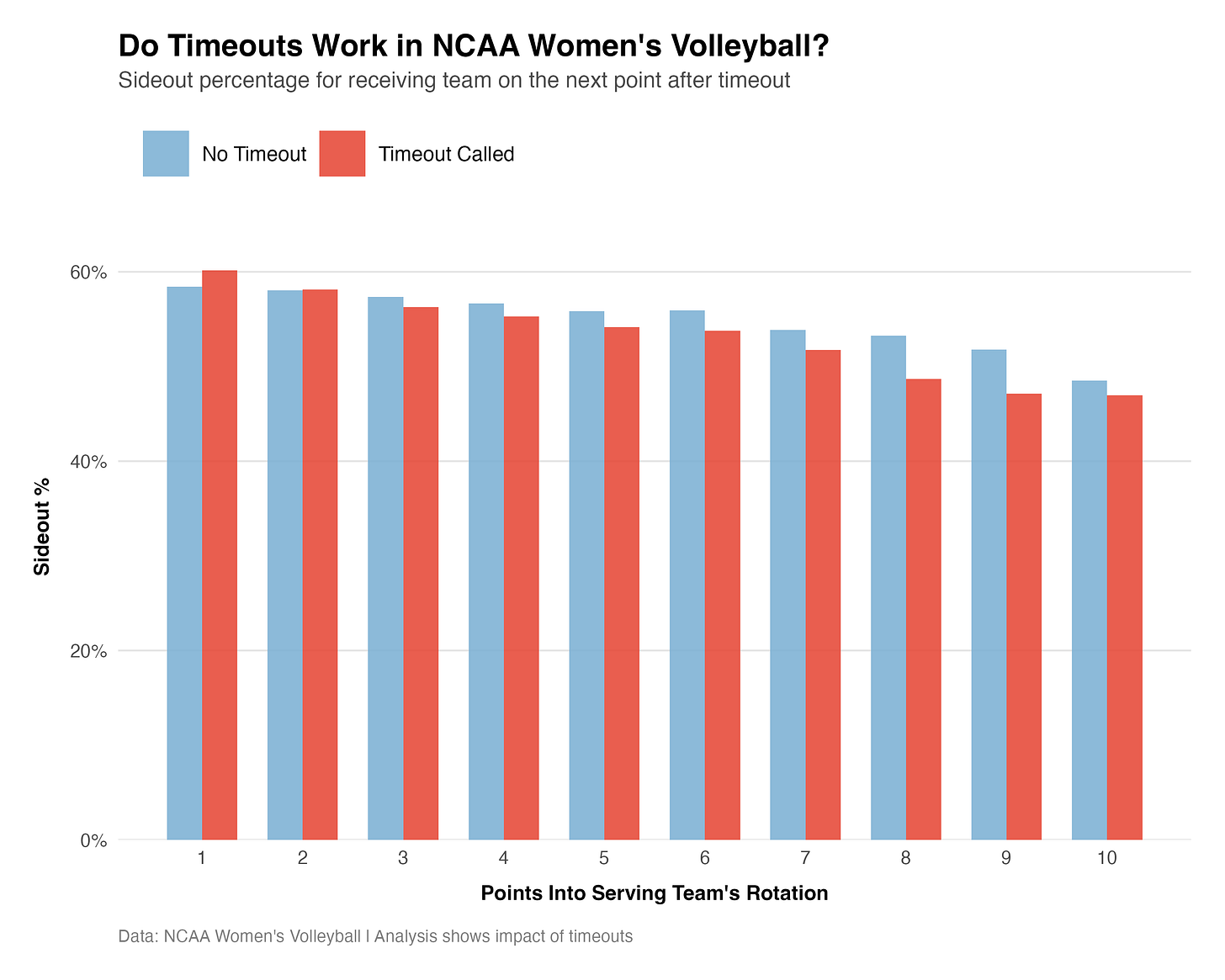

We’ll start first by looking at the result of the point immediate after the timeout, and whether there is any difference in sideout2 percentage (i.e. how often did the receiving team win the subsequent point).

Aside from the 1st point, where timeouts are infrequent and can’t really be considered a “run”, we see that sideout rate is actually worse for the teams that call timeouts.

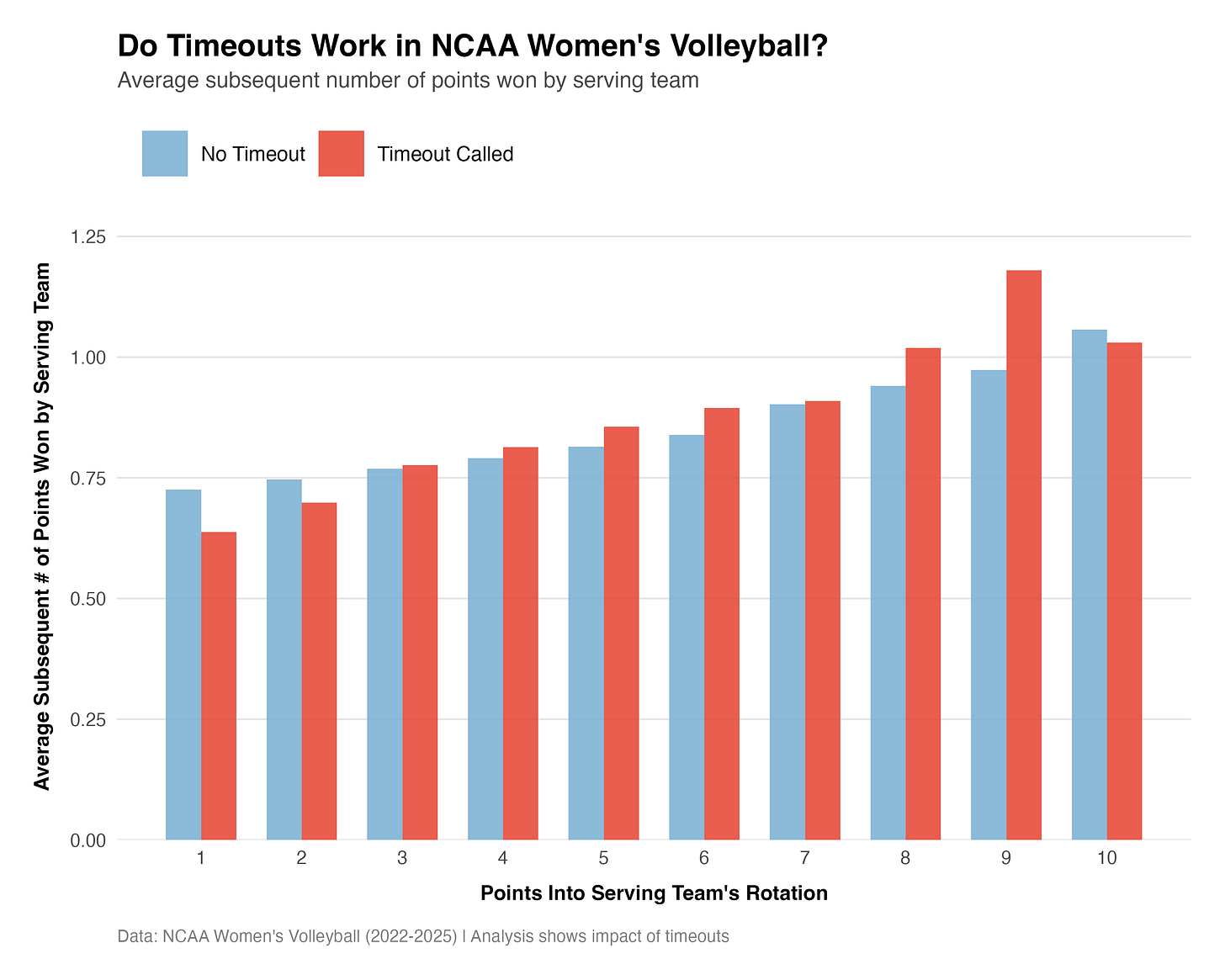

Rather than just focusing on the next point, we can also look at the average subsequent length of the service run, split by teams that took a timeout versus those that didn’t.

We get the same overall result here, indicating that in most situations, calling a timeout leads to longer opponent service runs. As a side note, a naive reading of this chart would conclude there is some sort of snowball/momentum effect in play, since the longer you’re into an opponent rally appears to be associated with longer future success on serve. In reality, this is just garden variety selection bias - teams that can generate a run of 7 straight service points are more likely to be the superior team, and thus more likely to score points in general, regardless if they’re “on a roll” or not.

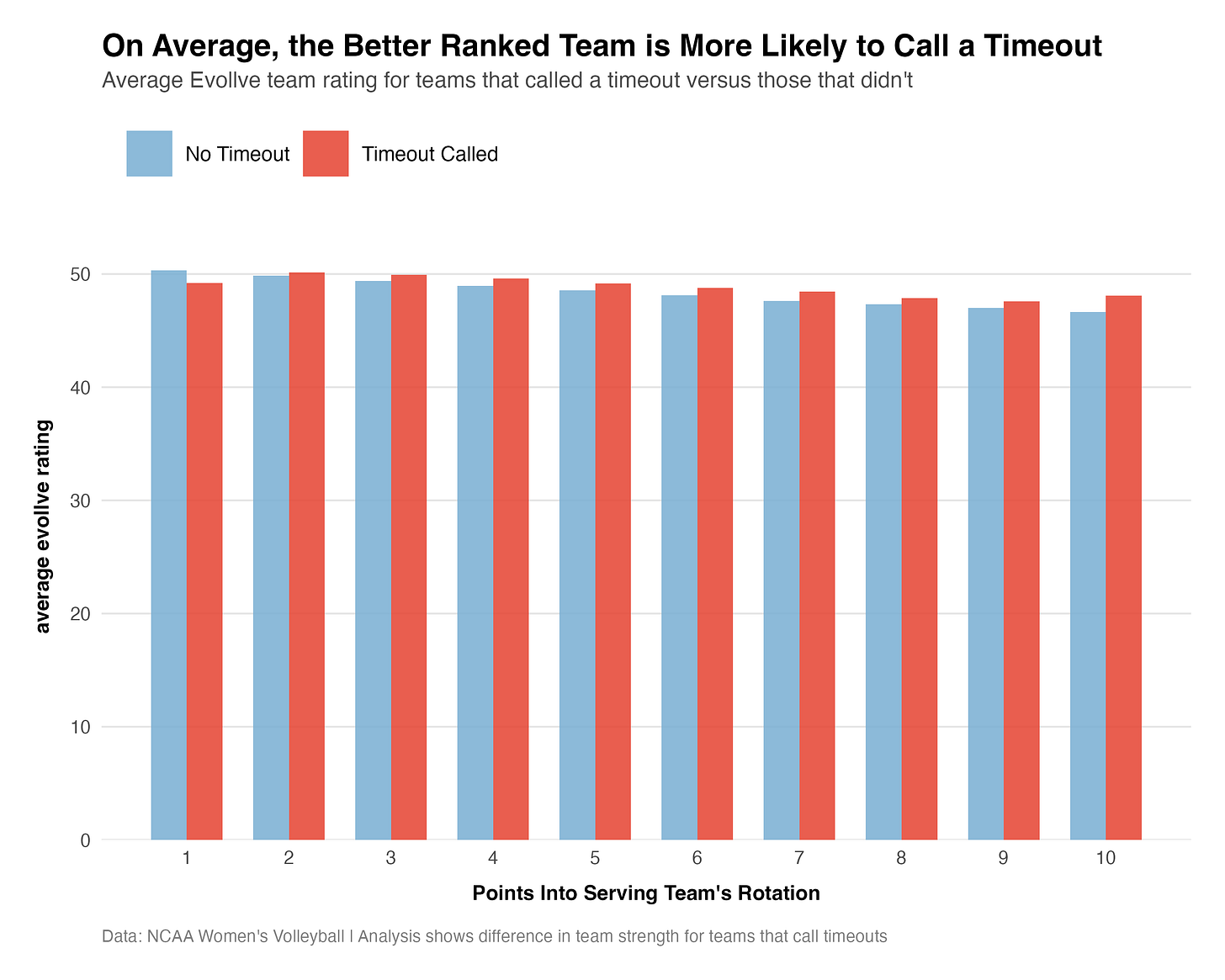

But speaking of selection bias, is it possible that is skewing the results above? What if inferior teams are more likely to call a timeout when facing a 5-0 run from an opponent?

The chart above shows the average Evollve team rating for both the “timeout” group and the “no timeout” group. Somewhat surprisingly, teams that call a timeout tend to be stronger. This means that if we accounted for expected sideout rate based on team strength, the adjusted impact of taking a timeout gets even worse in most scenarios.

Mind games

Another tactical use of a timeout is to “ice” the opposing team’s server, particularly when they’re facing a high pressure situation. There is evidence that players serve more conservatively in high leverage situations (fewer service aces and fewer service errors). If players are worried about losing a set or a match on their serve, calling a timeout, and letting them marinate in that anxiety, could be advantageous.

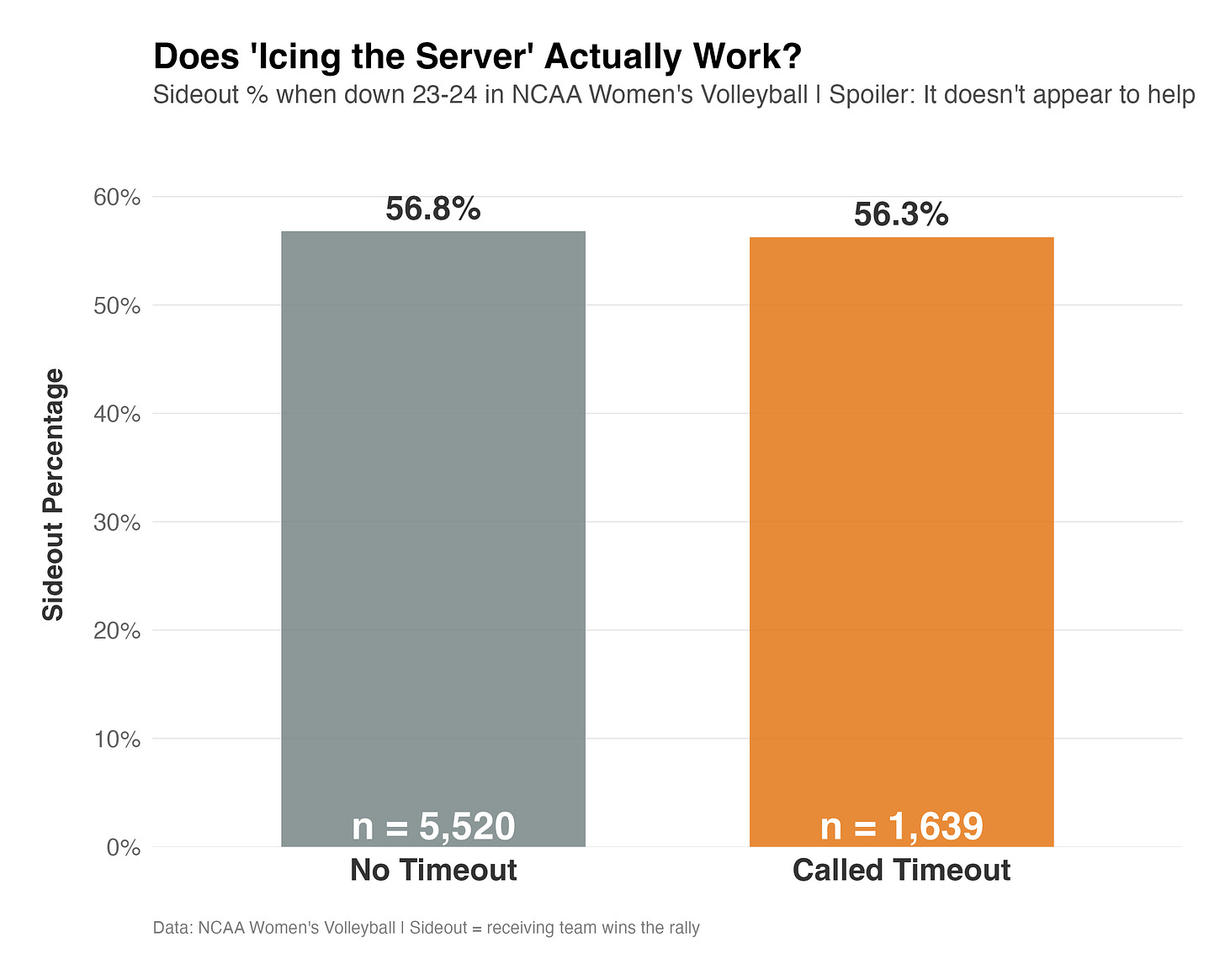

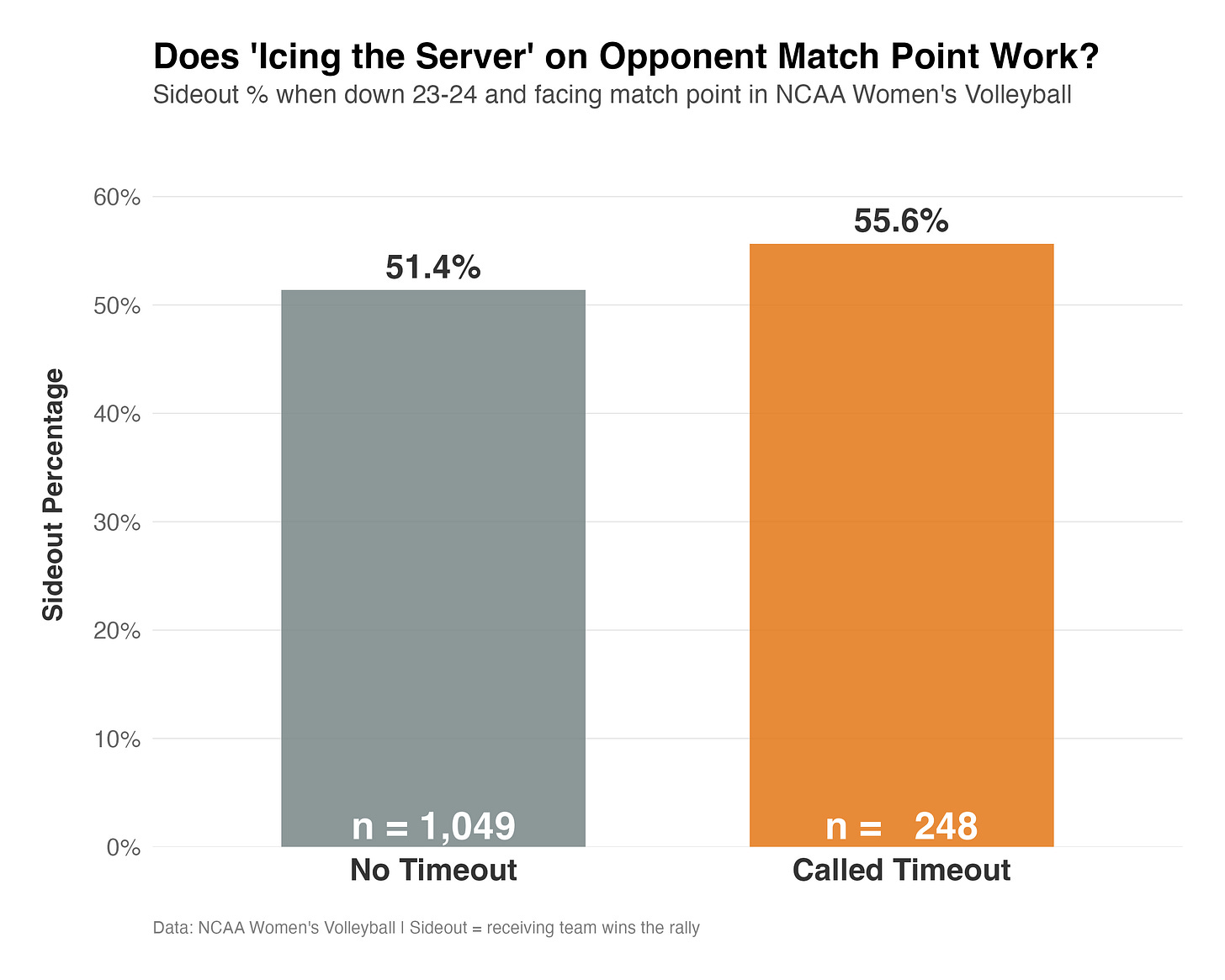

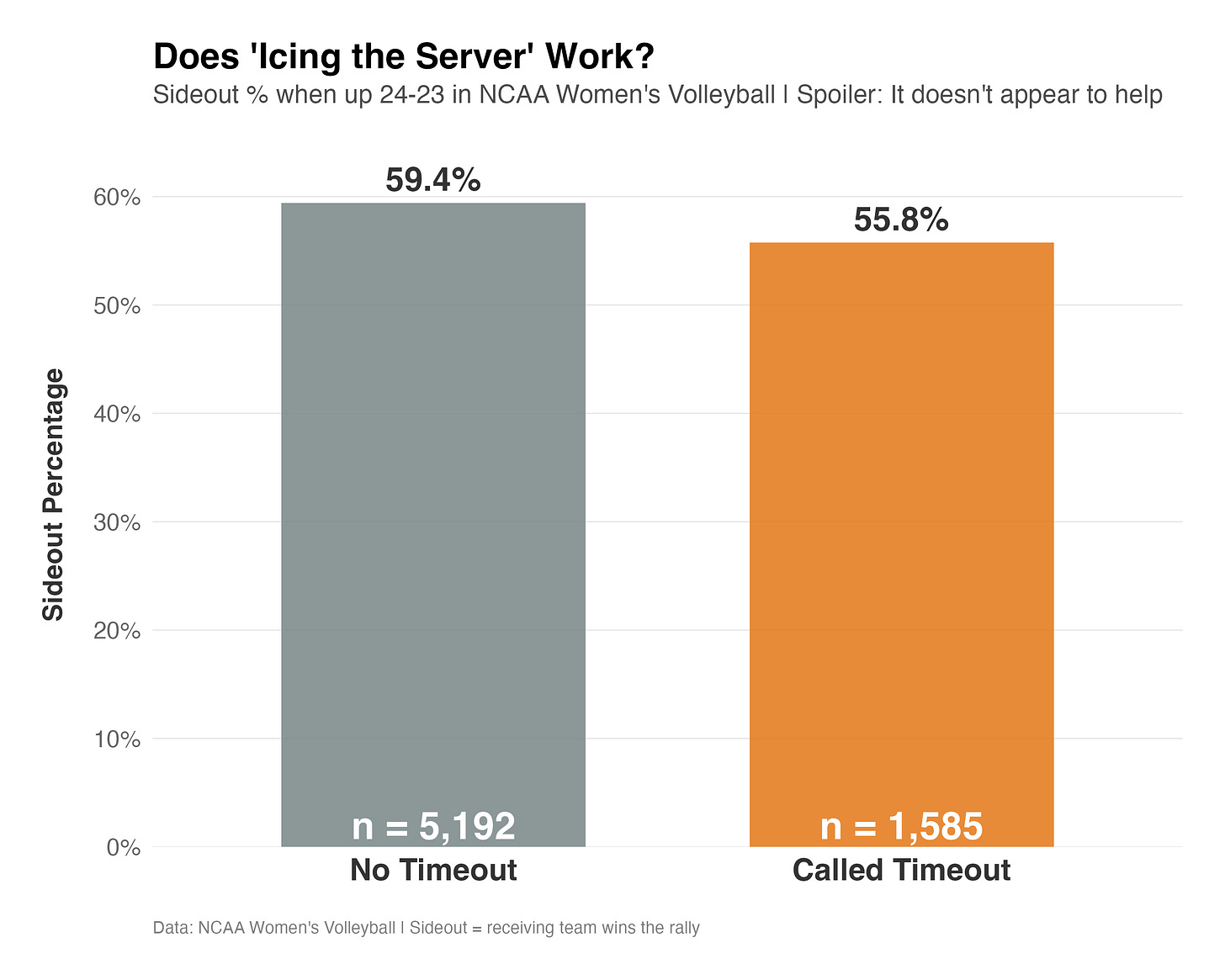

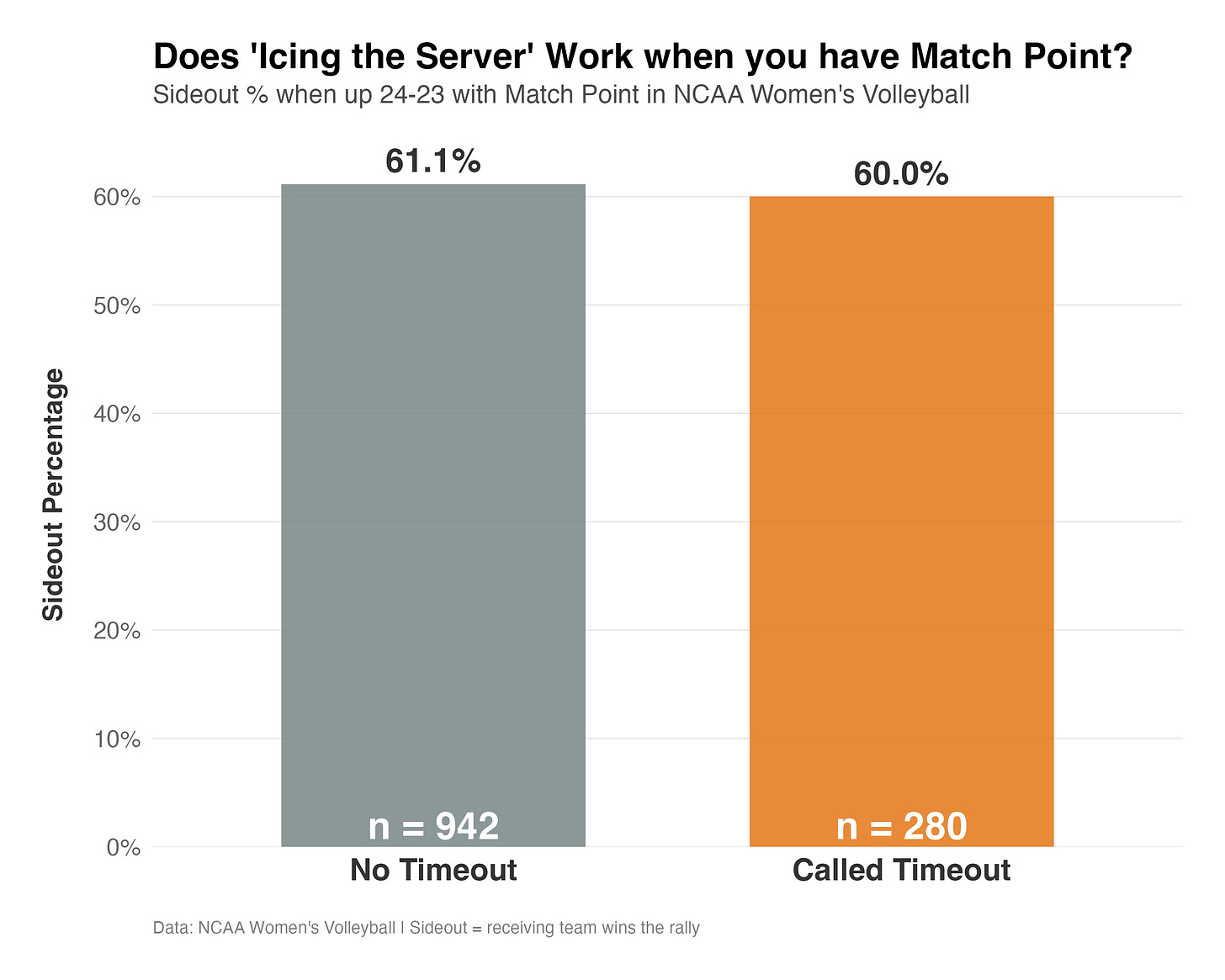

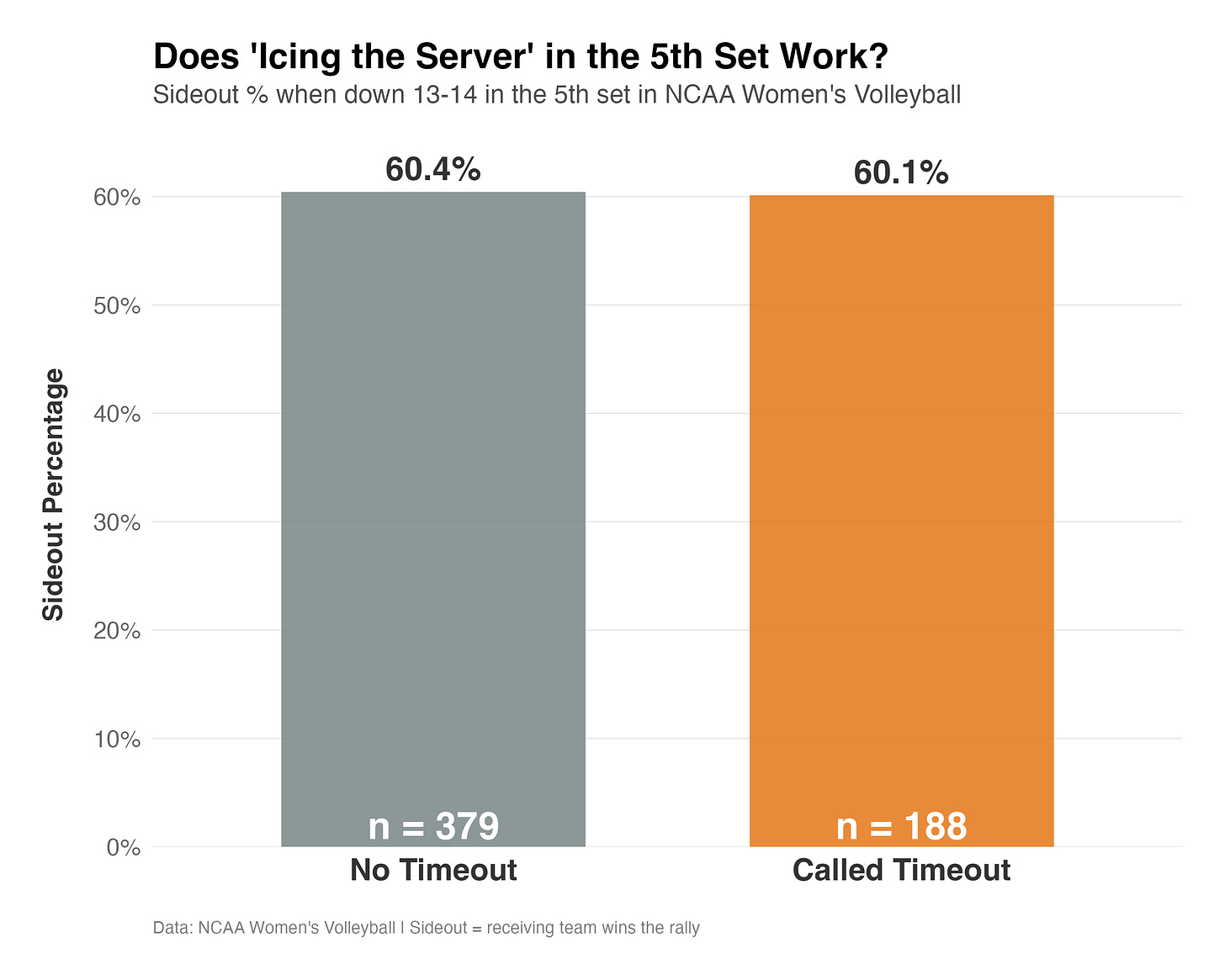

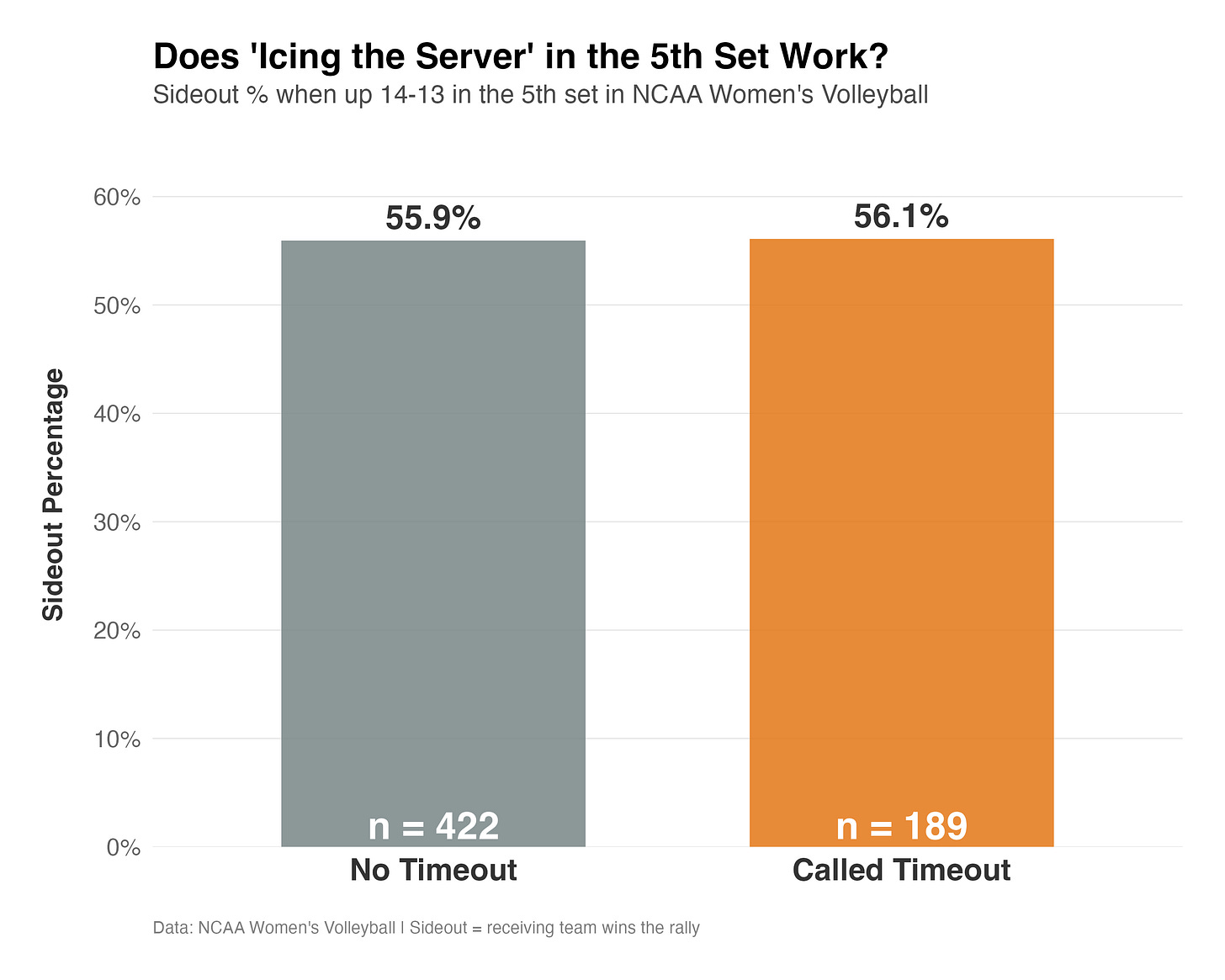

We’ll focus on the highest leverage points in a volleyball match, when the score is 24-23 in the first four sets, and 14-13 in the fifth set.

The charts below show the impact of calling timeout when your opponent is serving with a 24-23 lead, and then when your opponent is serving down 23-24. For both situations, we also take a separate view that only looks at the even higher pressure situation of match point.

Down 23-24 and facing opponent match point:

Here are the results for when the receiving team is up 24-23:

Up 24-23 with match point:

And finally, let’s go to the 5th set, looking at both being down 13-14 (opponent match point) and up 14-13 (your match point):

This is a lot of data without a lot of clear themes. My best read of the data is that, on balance, calling a timeout appears to hurt the receiving team ever so slightly in most situations. Although, slice and dice the data enough, and you can find situations where a timeout appears to help.

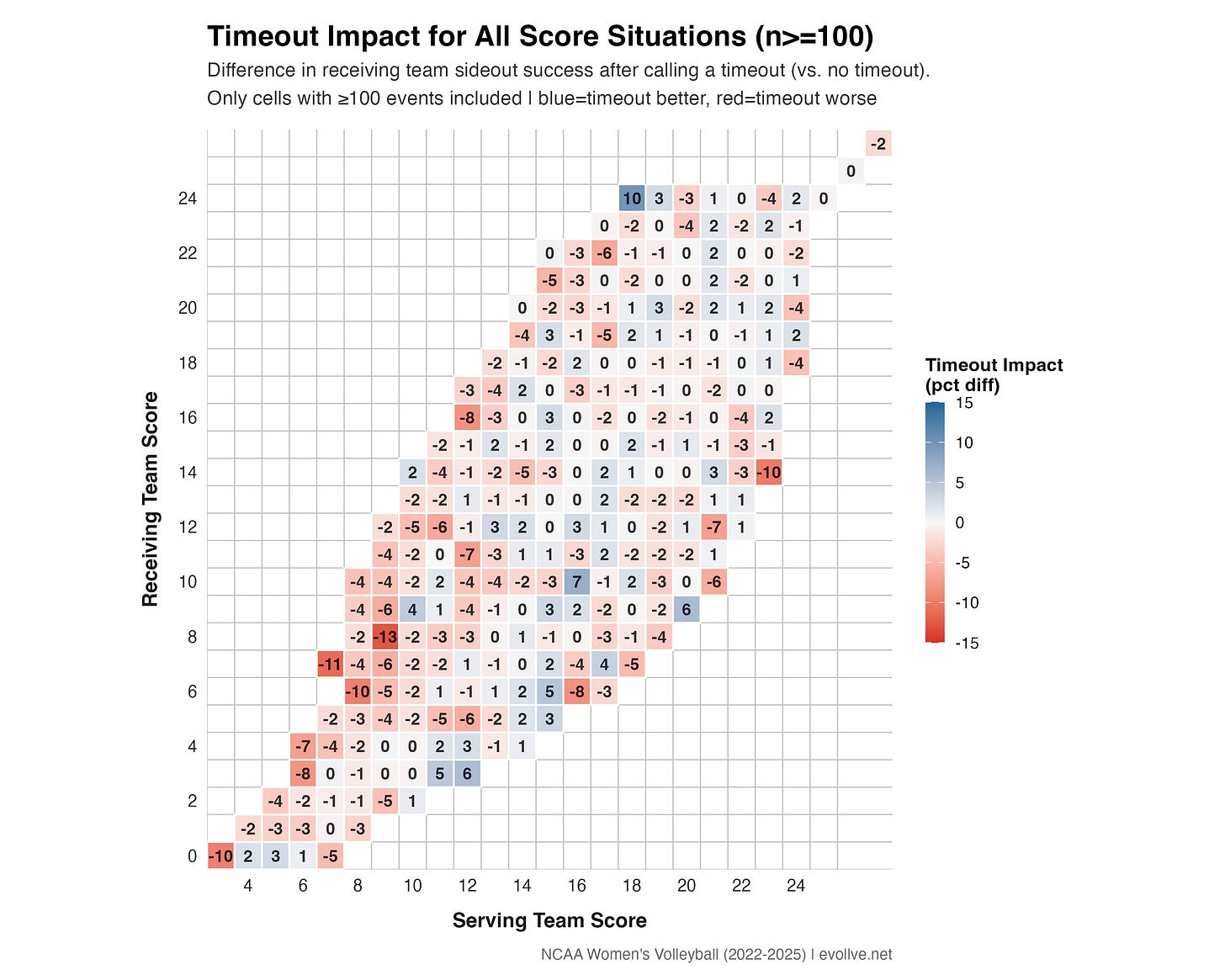

To that point, here are the results for all score situations (sets 1-4, n>=100):

Red (lower sideout % when calling a timeout) seems to dominate, but you can find pockets of blue here and there.

Conclusion

While I don’t doubt that timeouts have some sort of impact on the game of volleyball (I imagine some coaches are better than others at adjusting team tactics and motivating players during timeouts), there is very little evidence that it helps in the aggregate.

You could even argue, somewhat provocatively, that they’re counterproductive. My daughter’s high school team does a celebratory “T-O! T-O!” chant any time the opposing team calls a timeout in the middle of an extended scoring run. Perhaps calling a timeout demoralizes players by drawing attention to their inability to get a stop? Perhaps it’s better to let them stay in a flow state, and trust that the stop will come? Perhaps. But in general, it’s best to avoid the temptation to concoct “just so” stories such as this that involve armchair psychoanalysis of top-level athletes.

What this data does suggest though is that coaches should consider more non-traditional uses of timeouts, as the traditional use doesn’t seem to do much. Maybe it’s fine to call a timeout in the middle of one of your own serving rotations?

A nice thing about working with NCAA Division 1 Womens Volleyball data is that you rarely have to deal with “small n” problems.

Sideout is when the receiving team wins the point, and thus the serve. It is a term hardcoded into the jargon of volleyball, due to how scoring used to work. Prior to 2000, a team could only score when serving, so achieving “sideout” was a necessary step in the process of scoring.